Excesses in Inventory Management

Today, there are many inventory management programs that enable excellent results when ordering goods from external suppliers. They all rely on different metrics, algorithms, and methods. Which metrics are more important, and which management methods are most suitable—each company decides for itself, depending on its specifics. However, several key problematic phenomena can be identified that all companies face. One such phenomenon we would like to draw your attention to is “excess” or “excess inventory,” and we would like to share our experience in dealing with it.

This article will address:

- Definition of the concept of “excess.”

- Examples of the causes of excess.

- Consequences of ignoring excess inventory.

- Examples of solutions in situations where excess exists.

- The points discussed in this article are based on the experience of successfully completed projects implementing the ABM Inventory management system in various retail companies.

Definition of the concept of excess.

We propose the following definition of the phenomenon of “excess”: it is the quantity of inventory for a specific product at a particular sales point that exceeds the calculated optimal stock level.

Accordingly, the next question is how to calculate this “optimal stock level.”

To do this, the following metrics need to be determined:

- The replenishment time for a product at the sales point is the number of days from the moment of the current order to the delivery of the next order, after the current one. This parameter should consider not only the time from delivery to delivery but also the time required to fulfill the order.

- Average sales of the product during the replenishment time, in quantitative terms.

- The minimum quantity of the product that can be ordered. Some products are supplied only in packages, while others can be supplied individually, and this also needs to be taken into account.

Ultimately, by multiplying the replenishment time by average sales and adding the minimum order quantity, we arrive at the optimal quantity of product that needs to be maintained at the sales point. By “maintained,” we mean that orders should not exceed this calculated stock level; otherwise, the company will create excess inventory for itself.

This definition of excess inventory allows for high-quality analysis in any context—product groups/subgroups/positions, sales points, product-related specialists, and so on.

Causes of Excess Inventory

The main causes of excess inventory identified through the analysis of completed projects are:

- Unauthorized ordering of additional inventory by the purchasing manager, exceeding the calculated optimal stock level. This is perhaps the most common situation. Managers often justify such orders with their intuition, saying things like, “I feel this is necessary” or “Based on my experience…”. Unfortunately, according to analyzed statistics, such orders are erroneous in 80% of cases and serve as the primary cause of excess inventory.

- Purchasing large quantities of products from suppliers at a discount. This frequently occurs when a supplier attempts to “push” their slow-moving goods. As a result of such purchases, the sales point receives inventory that remains on the shelf as “dead weight,” selling poorly or not at all. There have been instances where a year has passed since the purchase, and less than a quarter of the stock was sold. With this trend, such stock may remain for several more years, creating excess.

- A similar situation occurs when a supplier buys or pays for shelf space for their products at the sales point, either temporarily for a promotion or on a permanent basis. This situation can seem ambiguous because the supplier is paying for the occupied shelf/additional quantity for the promotion. However, if the promotion performs worse than expected or the supplier’s product sells poorly, the sales point is left with stock that does not justify the space it occupies, even with the supplier’s payment. It’s also essential to consider that the primary asset of a retail network, aside from inventory, is the shelf. Maximum margin should always be sought from it, and when it is occupied by slow-moving products, the profitability per square meter of shelf space declines.

- Personal agreements between the purchasing specialist and the supplier. Unfortunately, this is a very real situation that sometimes occurs. It can be initiated by either the supplier or the purchasing specialist themselves. The essence is as follows: the specialist makes a purchase of goods that the supplier wants to get rid of in exchange for some form of compensation. The sizes of these batches vary, but considering that unwanted goods are sold this way (a desirable product would sell regardless), any such purchase adds excess inventory to the company’s warehouse.

- Delivery of more than the ordered quantity or items not included in the order by the supplier. This situation occurs less frequently but is worth mentioning. It usually happens with large national and/or international suppliers, making it challenging to dictate the terms of the relationship.

- The emergence of excess due to a sharp decline in demand. When demand drops, it’s necessary to reassess/recalculate the optimal stock level. In such cases, it’s possible for current inventory to remain above the new optimal stock level for some time. This is a natural phenomenon; however, it should be minimized by regularly reviewing the optimal stock levels to align with current demand at least once per season/quarter, and more frequently if possible.

Consequences of Ignoring Excess Inventory

Excess inventory is a concept that can be minimized, but it is extremely difficult to eliminate entirely. Therefore, a common stance may be taken that “excess will always exist, so why waste time analyzing it?” or “having more inventory than needed isn’t a big deal.” Such an attitude can lead to the following consequences:

- Each unit of product acquired beyond the optimal quantity sits “in reserve,” taking up valuable warehouse/shelf space. As long as this excess inventory remains unsold, it acts as “frozen” capital—funds that are not generating returns and do not contribute to profitability.

- Excess inventory carries a risk factor related to expiration—both physical (mainly for food products) and moral (for non-food products, technology, etc.). If demand trends change, it may happen that the current stock of certain products loses value or even becomes “unsalable,” meaning that money spent on these items was wasted.

- Having significant stocks of specific product lines limits the ability to expand the product range/portfolio. This restriction prevents the introduction of a broader spectrum of goods to attract more customers and, consequently, increase profits.

Examples of Actions in Situations of Excess Inventory

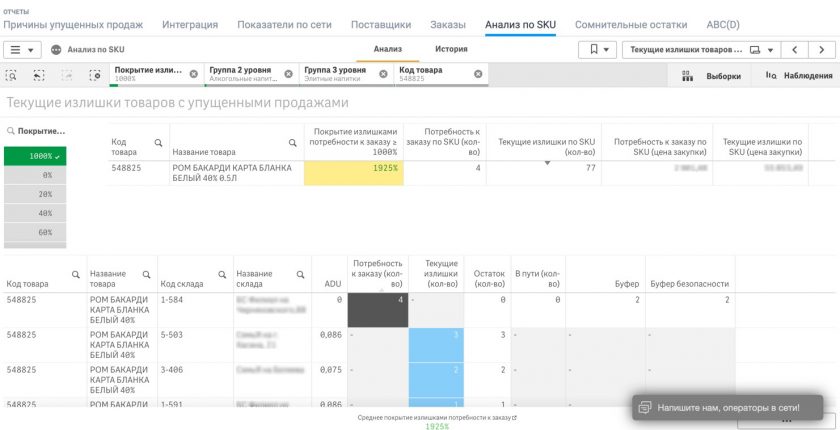

The first step is to conduct an analysis of current inventory. There are two primary directions to consider: excess inventory in quantitative terms and excess inventory in monetary terms. Often, organizations choose one direction and focus solely on it, neglecting the other. We recommend analyzing both directions and integrating the results to identify the most numerous excess items with the highest value. While this approach will naturally require more time and effort, such investments are justified. There are numerous practical examples where eliminating excesses of high-value but low-quantity items did not improve the utilization of storage/shelf space. Conversely, eliminating significant excesses of low-cost items did not yield the desired financial impact. It’s crucial to understand that the quality of the analysis directly affects the effectiveness of subsequent actions to minimize excess inventory.

Further grouping should be done according to the following principle:

- Excess inventory with a clear downward trend, meaning there are more or less regular sales.

- Excess inventory with very weak or no downward trend at all.

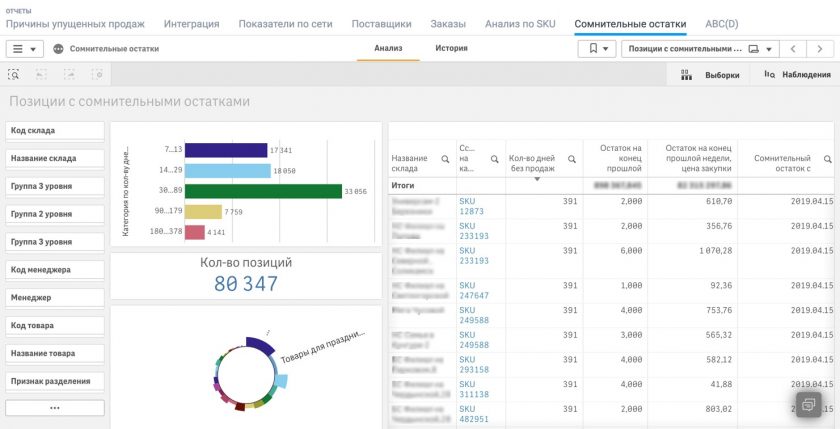

If the appropriate tools are available, a report on the lack of movement (sales) by product groups/subgroups/positions over a selected period will be very helpful in this categorization. Therefore, items that have been stagnant without movement for longer periods should be prioritized for elimination.

For the first group, the main goal is to identify the cause of excess inventory for specific product items and neutralize it. Once the problem is identified and resolved, one can either wait for the inventory levels to stabilize at the optimal point, taking into account the existing sales, or undertake additional marketing activities (advertising, promotions) to expedite the sale of excess inventory.

For the second group, the cause of excess inventory is secondary; the primary issue is the need to eliminate stocks of slow-moving or unsalable items.

How can this be done?

- Process returns to the supplier. If such arrangements were not previously established in the relationship with the supplier, additional agreements may be necessary.

- Food products and certain categories of non-food items can be used for the company’s internal needs, such as internal production, maintenance, and so on.

- Conduct an analysis of the sales of individual items across different retail locations. There may be situations where some locations have no sales and excess inventory, while others experience sales and even shortages due to geographical, social, or other factors. In such cases, stock from locations with no sales should be transferred to those with sales. This type of analysis is challenging to perform manually without specialized reports, but it provides an opportunity to liquidate excess inventory and generate profit.

Inventory relocation for redistribution or returns can also be organized in several ways. If a distribution center (DC) is available, all excess stock from retail locations can be consolidated there for further redistribution or return to the supplier. In the absence of a DC or if relocating goods to it is impractical due to geographical, logistical, or other factors, a retail location with suitable storage capabilities can be used as a “temporary DC” or “temporary internal warehouse.” The final option is the direct transfer of inventory from one retail location to another, but this is only advisable when the locations are in close proximity—within the same city, district, or region—and taking into account the product price and the margin it generates. Therefore, it is essential to ensure that the costs of moving do not exceed the profit that can be gained from selling that product.

After addressing the excess inventory in the second group, it is crucial to remove such items from the product range or assortment matrix (or any other document responsible for the assortment). If such a document does not exist, it should be created and maintained diligently—analyzing, reviewing, and updating regularly. This will help avoid mistakenly ordering non-liquid items and keep the assortment up to date.

Conclusion

Managing excess inventory is an ongoing process throughout the company’s operations, involving not only managers for specific groups but also the purchasing department head (or equivalent specialist) and even top management. If this metric is minimized in the current season or quarter, it does not guarantee that problems will not arise in the next. Whether you choose to follow the recommendations in this article or prefer to take your own approach, it is essential for the company to adopt a methodology for managing excess inventory that will be applied regularly and systematically to address this issue.